Sunday, November 30, 2014

Saturday, November 29, 2014

Background for Reading A Spy Among Friends

I am reading A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal by Ben Macintyre. Philby became a Soviet Spy in 1934, and from 1937 to 1939 he worked in Spain reporting the Civil War for British media (and to Moscow via his controllers). He worked as a foreign correspondent again with the British Expeditionary Force in late 1938 until Dunkirk and then again in France until its surrender.

Philby was then inducted into British Intelligence. He provided the USSR with intelligence that it would be invaded by Germany (which was not believed) but not by Japan (which was believed, and allowed Stalin to move troops from the East to the defense of Moscow). He was in late 1941 put in charge of the section of MI6 that dealt with Spain and Portugal; later north Africa was added to that section's responsibility. As he rose in the British Secret service, and as his credibility increased in Moscow, his importance as a Soviet Agent also increased. He provide a huge amount of information to Russia during the war, and much of it went directly to Stalin himself.

In February 1947, Philby is put in charge of British intelligence in Turkey where he provides information to the USSR on British and American efforts to destabilize Albania and Georgia. In 1949 he is moved to Washington, where he serves as liaison between British and U.S. intelligence agencies; in that position he provides intelligence of great value to the USSR. However, in 1951 Philby warned McClain and Burgess of MacClean's impending arrest as a spy; when they defected to Russia, Philby himself came under suspicion. Under that cloud, he resigned from MI6 in 1951.

In 1956 he was sent to Beirut as a correspondent for The Observer and The Economist; under this cover, he was reemployed by MI6 as an agent. However, more evidence accumulated against him, and in 1963, under interrogation, he made a partial confession; he then defected to Moscow.

Things I Thought to Research While Reading

Kim Philby was born on New Year's Day 1912 in India, the Jewel in the crown of England's empire. That empire actually increased in size as a result of World War I. In the aftermath of World War II, however, the empire fell apart. In the east, India, Pakistan, Burma and Malaysia all gained independence by 1963. Britain's position in the Middle East was diminished by the partition of Palestine in 1948, Egyptian independence in 1952 and the Suez Crisis in 1956 (which also led to the independence of Sudan); in 1968 Britain announced it would withdraw military bases east of Suez, and had done so by 1976. Britain's African colonies continued to gain independence with most independent by the late 1960s. Britain applied for membership in the decade old European Common Market in 1961, and succeeded in achieving membership in 1973. Thus in Philby's lifetime Britain had ceased to be in command of a global economic and political empire and become instead one of a number of nations combined in a new western European political and economic entity.

Philby was born into the British elite, and was the product of an exclusive public school (Americans read that as private school) and Cambridge University. Post war Britain was quite different than the interwar society in which he grew up. In 1945 the Labor Party gained power and held it for six years; after the war, England lived through a decade of austerity. By the 1960s, "reforms in education led to the effective elimination of the grammar school. The rise of the comprehensive school was aimed at producing a more egalitarian educational system, and there were ever-increasing numbers of people going into higher education." The 1950s and 60s saw a rise in immigration to Britain, primarily from former colonies, and an accompanying rise in racism. While Philby's MI6 remained relatively elitist, MI5 became much more an organization of middle class people.

Macintyre's book does not deal in much detail with the global environment in which Philby's career took place. It seems to me that his role as a spy for the USSR was different during World War II and the Cold War. In the form, when the USSR and Britain were allies, Britain and the USSR faced an existential threat from Nazi Germany. During the Cold War, when Britain was engaged in an effort with the USA to contain the USSR. the threat from Soviet weapons of mass destruction and its efforts to expand Communist government globally appeared comparably existential to Britain.

It also seems to me important to note that the nature of the intelligence agencies was changing. In World War II sabotage was a major function; in the Cold War, espionage was perhaps the leading function. Moreover, technological improvements led to changes in the way information was gained by intelligence agencies. Signals intelligence became important as agencies were increasingly able to capture telephone and other communications. Aerial and then satellite remote sensing allowed intelligence agencies to literally see what was happening on the ground, with professionals becoming amazingly proficient in interpreting imagery. Computers augmented human capacity to deal with huge amounts of signals and imagery data.

It should also be noted that there has been a proliferation of other forms of intelligence. Of course the military continues to have strong intelligence services. The U.S. State Department has a Bureau of Intelligence, drawing on its strong cadre of political and economic officers. However, other agencies of government also gather information on trade, agriculture, climate, fisheries, health, and other topics.

As an aid to memory, here is a timeline of some of the events that bear on the story of Kim Philby, the double agent.

World War II

1938 Munich Pact and German Sudeten Anexation

The Anschluss

1939 Molotov-Ribentrop Pact

1940 German invasion of France and Low Countries; Dunkirk

1941 German invasion of the Soviet Union

1942 Battle of El Alemein

1943 Allied invasions of Sicily and Italian mainland

Battle of Kursk

1944 Normandy invastion

1945 VE Day

VJ Day

Cold War

1946 Churchill gave "Iron Curtain Speech"

Central Intelligence Group created in USA

Keenan wrote "Containment memo" leading to U.S. policy

1947 CIA and National Security Council created

Truman Doctrine announced opposing Communist expansion in Europe

U.S. provided $400 million economic aid to Greece and Turkey

1949 USSR tested its first Atomic bomb

NATO Treaty signed

Communists take over government of mainland China

1950 Klaus Fuchs and others who spied on U.S. Atomic bomb exposed.

1952 National Security Agency created responsible for signals intelligence

1953 Stalin died

1956 First U2 Spy Plane flight over Russia

Suez Crisis

1957 Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite, launched

1958 Explorer 1, the first U.S. satellite, launched.

1960 Gary Powers U2 Spy Plane shot down over USSR

1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion

1962 Cuban Missile Crisis

Labels:

book review,

History

Thursday, November 27, 2014

Wednesday, November 26, 2014

Support for Reading about Holmes' Great Dissent

I recently posted comments on The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind--and Changed the History of Free Speech in America by Thomas Healy. If occurs to me that it is hard to understand this book if one does not understand the times in which Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, wrote his opinions in 1919 that concerned freedom of speech.

Of course these were written in the aftermath of the First World War, known as The Great War at the time. Fighting had started in Europe in 1914, the United States had entered the war in 1917, and the Armistice had come in 11/11/1918. During the war there had been German sabotage in the United States, which had been widely recognized. Indeed, the war had fueled prejudice against large classes of immigrants:

In 1916, President Wilson warned against hyphenated Americans who, he charged, had "poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life." "Such creatures of passion, disloyalty and anarchy", Wilson continued "must be crushed out".American soldiers were returning in great numbers from Europe; they and U.S. soldiers who had not yet been sent to Europe were being demobilized by the million. They needed civilian jobs.

Blacks had migrated from the south to the northern industrial states in great numbers during the war, in part to take jobs in war production and jobs that had been left by men going into uniform. Thus Blacks too would be competing for jobs in ways that they had not before the war.

Foreign immigration to the United States was also important:

Throughout eastern and southern Europe after 1880, Poles, Ukrainians, Greeks, Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Jews, and dozens of other ethnic groups were fleeing repressive regimes in Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the Ottoman Empire, seeking both economic opportunities and personal freedoms in North America. Millions of others came from Britain, Scandinavia, Italy, and other parts of Europe. With very few restrictions on European immigration to the United States and a booming economy, immigration reached all-time highs in the decade prior to the Great War. Whereas immigration had averaged about 340,000 per year during the 1890s, between 1905 and 1914, it jumped to more than 1 million per year. Although Canadian policy was more restrictive, the trend was the same. During the 1890s, immigration to Canada averaged about 37,000 per year; between 1905 and 1914, the figure rocketed to almost 250,000 per year.Thus in the immediate aftermath of the war, large numbers of immigrants were also competing for jobs in the United States.

I some time ago read 1912: Wilson, Roosevelt, Taft and Debs--The Election that Changed the Country by James Chace. Teddy Roosevelt and Taft, both progressive Republicans, both wanted to be president. Taft won the Republican nomination, and Roosevelt ran as the candidate of the Bull Moose Party. Wilson, ran as a Democrat, but also as a progressive and won the election (as well as the election in 1916). Eugene Debs, running as a Socialist, received some 6 million votes. This was the high mark for Socialism in national politics. Justice Holmes himself was the target of an anonymous bomb sent through the mails -- one of some 30 letter bombs attributed to anarchists.

World War I had also led to the fall of several empires, and to the rise of Bolshevik government in Russia. With increasingly grave doubts about the ability of monarchs and aristocrats to govern, democracy, socialism, Bolshevism, and anarchism were all in the air; fascism was soon to follow. It is perhaps not surprising that those holding power in the United States were concerned about the spread of ideas antithetical to those on which the USA had been founded.

There was a recession after the war.

After the war ended, the global economy began to decline. In the United States 1918–1919 saw a modest economic retreat, but the next year saw a mild recovery. A more severe recession hit the United States in 1920 and 1921 (see: Depression of 1920–21) when the global economy fell very sharply.This must have further complicated the employment picture as black and foreign immigrants competed for jobs with servicemen returning to private life and the job market.

The Ku Klux Klan had been reborn in 1915 as an organization of white, native-born American, Protestant men. Opposing Catholics, immigrants and blacks, it achieved a membership of some five million in the 1920s, perhaps one-third to one-half of all eligible Americans.

The summer of 1919 was known at "the Red Summer".

The Red Summer refers to the race riots that occurred in more than three dozen cities in the United States during the summer and early autumn of 1919. In most instances, whites attacked African Americans. In some cases many blacks fought back, notably in Chicago, where, along with Washington, D.C. and Elaine, Arkansas, the greatest number of fatalities occurred.

The riots followed postwar social tensions related to the demobilization of veterans of World War I, both black and white, and competition for jobs among ethnic whites and blacks. The riots were extensively documented in the press, which along with the federal government conflated black movements with bolshevism.This was also the time of a government move against purported immigrant radicals.

The Palmer Raids were attempts by the United States Department of Justice to arrest and deport radical leftists, especially anarchists, from the United States. The raids and arrests occurred in November 1919 and January 1920 under the leadership of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. Though more than 500 foreign citizens were deported, including a number of prominent leftist leaders, Palmer's efforts were largely frustrated by officials at the U.S. Department of Labor who had responsibility for deportations and who objected to Palmer's methods. The Palmer Raids occurred in the larger context of the Red Scare, the term given to fear of and reaction against political radicals in the U.S. in the years immediately following World War I.The Palmer Raids are thought to have been an early important boost to the career of J. Edgar Hoover.

Perhaps this situation in 1919, and especially the summer of that year, encouraged Justice Holmes towards a more favorable position towards freedom of speech. His "great dissent" was published in November of 1919.

Labels:

book review,

History

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Higher Education After 2015

I was asked to comment on the question “What will 2015 mean

for higher education? Where are we coming from, and where are we going?” 2015

marks the end of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals and also the

end of the Education for All effort, so there has been an effort to consider

what if anything should be put in place after 2015 as goals and objectives in

international development.

It is almost 60 years since I entered engineering school as

a freshman. The world of the student has changed completely since that time.

The tools of the engineer have changed, as has the task of the engineer.

Indeed, there are whole fields of engineering now that did not exist then.

Still, a knowledge of mathematics and language are still fundamental, as are

understanding of how to analyze and synthesize.

A decade later I started working in a University computer

center in Chile. The machine there was much less powerful than the decade old

machine in my home on which I am writing this. My first job was to get software

for the simplex algorithm for linear programming and PERT chart calculations up

and running. I had undocumented binary decks of cards with the programs, not

debugged, from the users group to start with. There were no journals, few books

and few colleagues with any computer experience. When I taught Fortran the next

year, I had to write and mimeograph a manual for my students – there were none

available in Spanish.

The changes are obviously huge. Higher education has

expanded greatly in recent decades, both due to an increased demand from

qualified students and to an increase in the number of institutions of higher

learning offering educational services. The role of the private sector has

increased. Higher education has diffused from rich countries to former

colonies, and globalized with many more students studying abroad. There has

come to be a huge problem of quality – great universities are not built

overnight. The promise of new technology and new insights into learning has

become apparent, but in my view it has not yet been fulfilled.

As I think of higher education in the United States, in

Brazil, in China, in India, in Western Europe, and in Africa, I suspect that

the differences are greater than the similarities. Certainly the economic

resources for higher education are very different from country to country. If

the role of institutions of higher education is not only education, but

knowledge creation and organization, and service to the community, then the

challenges faced in India are different than those faced in the Russian

Federation, Mexico or Uganda. I think it important to recognize that each

country has to recognize its own challenges, opportunities and resources for

higher education; global benchmarks may not be very helpful.

We are a quarter century after the end of the Cold War, but

the specter of conflict is still with us. A challenge remains in the 21st

century to build the defenses of peace in the minds of men. Climate change now

seems inevitable, and the world is challenged with thinking through how to

limit its extent and ameliorate its impact. It appears now that population

projections were too optimistic, and the challenge of feeding an ever growing

population with limited land and water resources and changing climate is even

more daunting. Poverty remains a huge global problem, and the inequality of

income and wealth militates against economic progress. Thus the future presents

huge challenges for all countries, and all countries will be looking to their

institutions of higher education for help in meeting those challenges.

A Metaphor

“What should any well educated person know?” If one asks

that question I think there would be some common grounds. A well educated

person should command at least a native language and possible another tongue,

should have some facility with mathematics and some knowledge of geography, science,

books, and culture. But I suggest that once you got down to details, the answer

would be different in Japan than in China, in India than in Pakistan, in Brazil

than in the United States, in England than in France. However, that to me seems

a fundamental question that should be asked in each country as it looks past

2015 and plans for the development of higher education.

Clearly the institution of higher education should and must

provide different learning experiences for someone who will become a

professional historian, versus a physician, an architect, lawyer, or teacher.

Perhaps one might think of the common core that any well educated person should

command as the trunk of a tree, from which different branches extend. Those

branches grow. The body of world knowledge today is much greater than when I

began my university education; of course, some branches have died and been

pruned from the curriculum, while others have ramified (thus aeronautical

engineering has changed to include space technology). But the tree must

continue to grow and ramify, with a canopy expanding as human knowledge

expands.

In this metaphor, the tree is rooted in the culture of the

country and the social and economic needs it recognizes that its institutions

of higher education must fulfill. Higher education is dependent on the economic

and human resources it obtains from that general society in which it is rooted.

It may benefit from material from the global higher education system grafted

into its structure.

Education

Education is a human right, but how much schooling must a

country provide to its citizens gratis? How good must that schooling be? That

seems to me to be a decision that must be by each country for itself. Clearly a

rich country can provide more schooling on average to its citizens than can a

poor country. I enjoyed the right to attend university virtually free as a

young man, at campuses of the University of California, because the people of

California treated that as a right for its people; that allowed me to study at

very low cost through the level of PhD. California no longer makes that choice.

I would guess that a rich country can

also provide a wider variety of school choices to its citizens than can a poor

country; one country may choose to train concert level musicians or artists of

international caliber at government expense (choosing the most talented

applicants for such government grants) while another may not choose to do so,

perhaps finding it can not afford to treat such aspirations as rights of its

citizens.

Schooling is also an investment. The return to the society

for training some professionals is so high that that investment is more

cost-effective than other investments. Here we are talking about higher

education, and investments in schooling in institutions of higher education. The

investment in training people trained to quickly detect and stop outbreaks of communicable

disease, before they become epidemics is one such investment. So too is the

investment in training people to build and maintain the infrastructure that the

nation needs – roads, ports, airports, electrical power, dams, canals, railroads,

etc.

Schooling is also a service that a country can provide to

those willing to pay its cost. The citizen who wishes to take a management

course in order eventually to enable a transfer to a more responsible job in

another country may well be able to finance that training personally or have an

employer do so; I see no reason why a country might not provide such

opportunities, and no reason why they should be subsidized by the government.

Another person may chose to study French poetry, Japanese painting, or Russian

ballet; perhaps such course might be offered if a sufficient number of students

exists for their justification, but again perhaps a country can justifiably decide

that they must be funded privately.

The Creation and

Organization of Knowledge

Knowledge can and should be shared internationally, but it

has become clear that some knowledge is site specific. Examples might include

knowledge of Andean crops, tropical forests, or the ecology of the Great Lakes

of Africa. Institutions of higher education in all countries may choose to

contribute to the global stock of scientific and technological knowledge, as

well as knowledge of history and culture, and their governments may choose to

support that work as part of a national responsibility. However, there are

areas of knowledge in which universities and other institutions of higher

learning must invest, because they are vital to the people that they

serve. Clearly Ebola must be studied in

Africa, where it is found, and the genetic diversity of quinoa and other Andean

crops is best studied in the high Andes. Of course, research of these kinds is

relatively useless unless it is published, and unless it is communicated in an

intelligible manner to those who can utilize the results. Thus a university

agriculture field station, creating knowledge of greatest utility to local

farmers, must publish its findings and is best operated in conjunction with an

agricultural extension service.

A traditional area of

work for people in institutions of higher education is the writing of text

books, organizing knowledge for the students it serves. So too, faculty must

translate the literature of other nations into that which can be understood in

their own. Faculty members are often the gatekeepers, seeking out information

from other countries and introducing it to their own. They design curricula

which organize old and new knowledge, traditional and modern understanding, and

materials from foreign and domestic languages, providing the teaching materials

and aids that make the new synthesis available to their country’s students.

Service

I come from a country, the USA, in which service to the

community is generally accepted as a responsibility of universities. It is not

always so, and I feel that the university-community linkage should be

strengthened. I do so in part based on personal experience.

Many years ago, working in a technical university computer

center, I helped faculty provide services to the community. We conducted an

operations research effort in one company, showing it how to greatly expand its

business. In another case we discouraged a company from adding to an already

overly complex product line. In a third case, we encouraged a company to focus

more attention on its production facilities which were in fact the limiting

factor in its growth, and less on its marketing. Thus a university can provide

services to the private sector.

In that same setting we helped a local government to

schedule its traffic lights, and helped the national electric company to better

plan the location of its power lines and to decide whether to build an

integrated power generation and water desalinization plant. In another country,

years later, my graduate students helped the local health officials evaluate

alternative sites for a new major hospital. Other students helped the same

officials evaluate the pharmacy policies used in the network of health centers

in the region, suggesting major improvements.

What then Would I

Suggest?

The world is generating knowledge quickly. It is also

becoming a more complicated place, in which huge challenges are must be met.

Countries must utilize their higher education resources to meet the challenge.

Of course, part of the effort will be to continue to expand higher education to

meet increasing needs and demands for educational services, creation and

organization of knowledge and service to society. That means in all probability

not only more “bricks and mortar” but also more professors, instructors, and

support personnel.

There will be a need for more emphasis on continuing

education and education of adults; the world is changing, and people need to

keep up. They will need to adjust to faster changes in the workplace and in

careers, to faster changes in the economy, and indeed to changes in the

physical environment. An ever increasingly urban population will be expected to

need and want more information.

It seems to me that the organization of higher education

will have to change. Financing will have to be rethought and restructured in

many countries. I am a fan of the U.S. system of two year colleges which

prepare some students for paraprofessional careers and prepare others for

further education in universities; I hope other countries will consider

building networks of these institutions.

There is a huge task facing developing countries in

improving the quality of higher education. That task is not only complicated by

the lack of financial and human resources, but also by the simultaneous need to

expand.

Higher education will need to expand the use of science and

technology in accomplishing its own missions. It will need to draw on advancing

understanding of how people learn. I fully expect that information and computer

technology will become a more effective aid to the educator, the researcher,

and the provider of services to the community. I would also expect that the

social sciences will play a greater role in helping higher education

institutions understand their role in society and improving their function in

that role. Management science will help to better organize universities and

improve their service orientation.

A central role for the institution of higher education is,

ultimately, the promotion of cultural change. Yet this is also potentially the

most dangerous of its activities. Fortunately, institutions of higher learning

are the natural home of the humanities and of public intellectuals. They must

find a way to help preserve cultural heritage, be informed and led by cultural

leaders, and sensitive to the potential for doing damage to their cultural

matrix, while at the same time helping a culture to adapt as it must to

changing circumstances. The political realities of the necessary promotion of

change, and the education of a new generation of men and women to live actively

in a changing world, must be met and successfully navigated.

I can only wish the best for the educators, and especially

university educators in the 21st century!

Labels:

education

Monday, November 24, 2014

Chikungunya

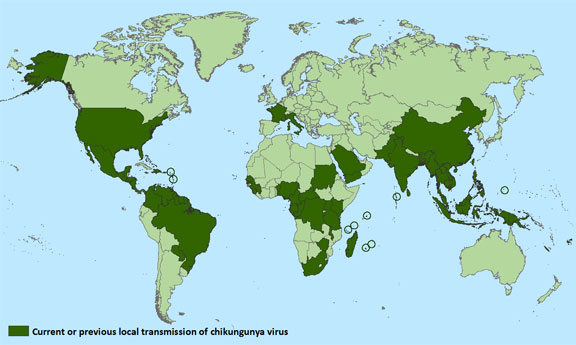

Chikungunya is a viral disease spread by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. Thus it is a disease that is especially problematic in places where those mosquitoes are common -- the humid tropics. There is no treatment or vaccine and the first human clinical trials are at least several years away.

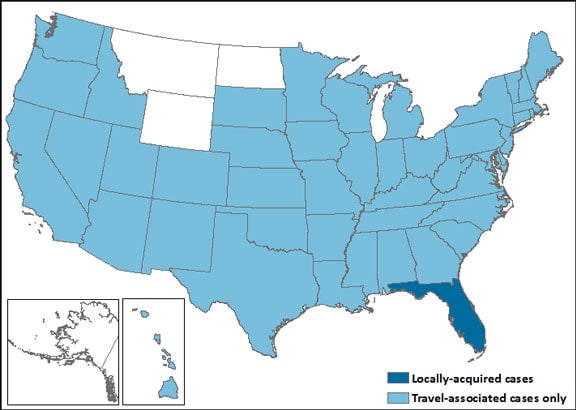

Since the first case was identified in the Western Hemisphere (in Saint Martin) last December, nearly a million cases have been reported in the Caribbean and Central America. It is epidemic in the Dominican Republic, Haiti and El Salvador. An outbreak apparently has been contained in the United States.

“Chikungunya” means “bent over” in the Makonde language. The name describes the stooped appearance of those with joint pain caused by the disease. Patients commonly suffer painful and swollen joints, fever, headache, fatigue and a rash -- symptoms that usually disappear within three weeks. However, arthritis, especially in the wrists and hands, can last for months, or years in some people, causing long-term disabilities. The virus can also cause diarrhea and vomiting, mouth ulcers, visual problems and meningitis. The disease poses the greatest threat to vulnerable groups including elderly people, babies, pregnant women and those with existing conditions such as high blood pressure or diabetes. (People at high risk might consider avoiding travel to places in which Chikungunya is known to be present.) About 150 people have died so far in this epidemic, a low case fatality rate. Still, the Chikungunya epidemic is a major public health problem in this hemisphere.

Travelers can protect themselves from the disease even in areas where it is prevalent by preventing mosquito bites. When traveling to countries with chikungunya virus, use insect repellent, wear long sleeves and pants, and stay in places with air conditioning and/or that use window and door screens.

Read more: in The Guardian and from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention

(as of November 18, 2014)

|

| *Does not include countries or territories where only imported cases have been documented. |

Chikungunya virus disease cases reported by state –

United States, 2014 (as of November 18, 2014)

|

| Add caption |

Labels:

Health

Sunday, November 23, 2014

Saturday, November 22, 2014

Silent Cal said it well!

If all men are created equal, that is final. If they are endowed with inalienable rights, that is final. If governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, that is final. No advance, no progress can be made beyond these propositions. If anyone wishes to deny their truth or their soundness, the only direction in which he can proceed historically is not forward, but backward toward the time when there was no equality, no rights of the individual, no rule of the people. Those who wish to proceed in that direction can not lay claim to progress. They are reactionary. Their ideas are not more modern, but more ancient, than those of the Revolutionary fathers.

Calvin Coolidge

Speech in Philadelphia on July 5, 1926, to mark the 150th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence

Labels:

Human Rights,

quotation

Wednesday, November 19, 2014

Did Multiethnic Empires Expire in the 20th Century?

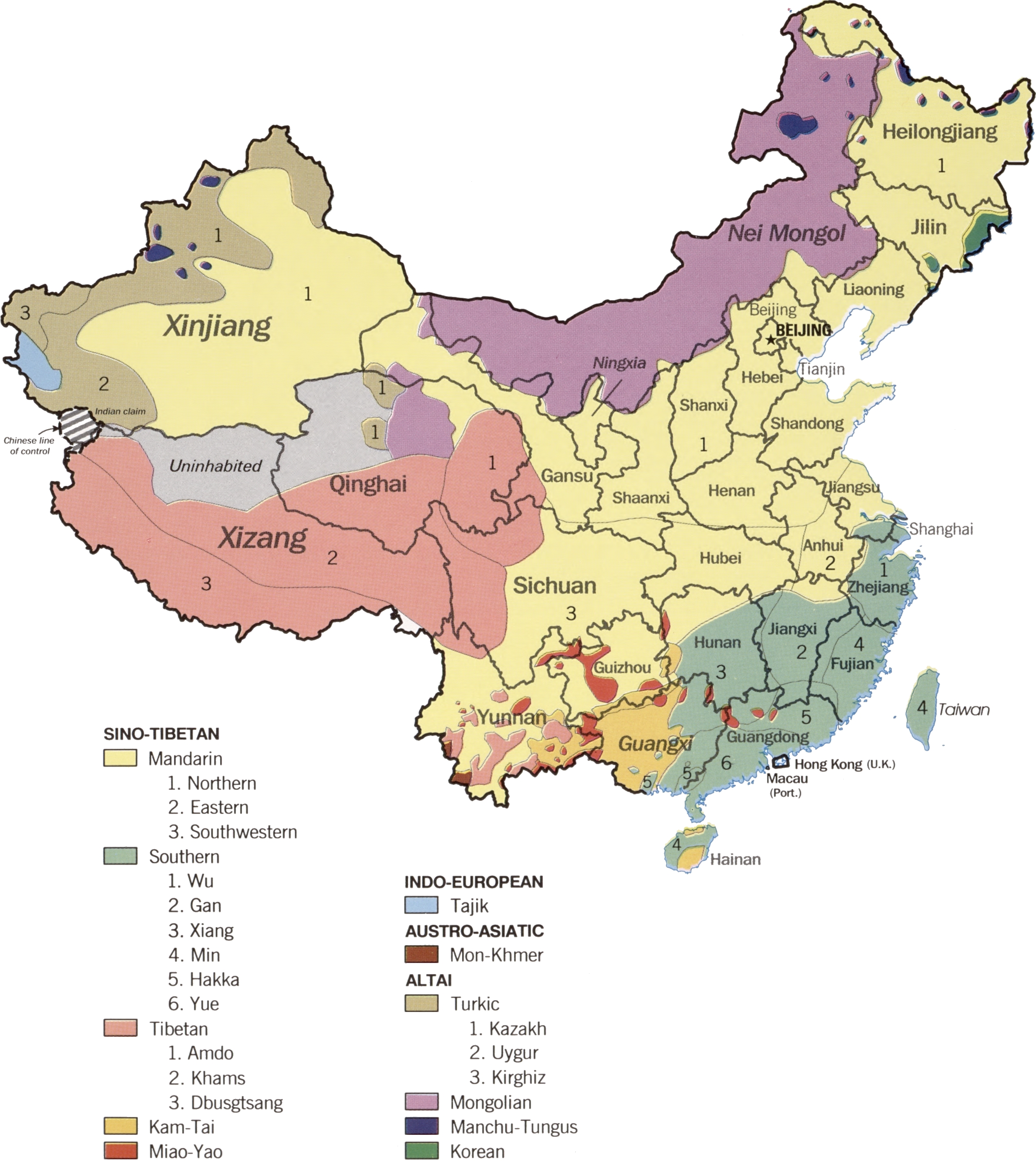

China

China's languages

Most people know that Mandarin Chinese — the official dialect used and promoted by the Chinese government and taught in most Western Chinese courses — is just one of many, and that a variety of other dialects (Cantonese, Shanghainese, Taiwanese, etc.) have millions of speakers as well. The above map illustrates the geographic distribution of the various dialects on mainland China and Taiwan. But perhaps less well known is exactly how different the dialects can be. They use the same character set, and most use Mandarin in writing, but the spoken dialects are often mutually unintelligible. As University of Wisconsin linguist Zhang Hongming once told the New York Times, "The degree of difference among dialects is much higher than the degree of difference among European languages."

India's languagesAs we have seen ethnic separatist movement recently -- Scotland, Wales, Catalonia, Kurds, ISIL, Libya, Sri Lanka, and Ukraine come to mind -- one wonders if we will see further separation in the two most populous countries of the world.

Just as many of China's most populous cities (Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong) are located in regions where dialects other than Mandarin prevail, many of India's biggest cities (Mumbai, Bangalore, Kolkata) are in states where Hindi does not dominate. This map is a bit outdated — Andhra Pradesh was split up this year, with the city of Hyderabad going to the new state of Telangana — but it's a good indication of the levels of linguistic diversity in the country, which speaks about 780 languages total, and has lost 220 in the past fifty years.

Labels:

foreign policy

Tuesday, November 18, 2014

"Rich countries are deluged with data; developing ones are suffering from drought"

I quote from an article in The Economist:

AFRICA is the continent of missing data. Fewer than half of births are recorded; some countries have not taken a census in several decades. On maps only big cities and main streets are identified; the rest looks as empty as the Sahara. Lack of data afflicts other developing regions, too. The self-built slums that ring many Latin American cities are poorly mapped, and even estimates of their population are vague. Afghanistan is still using census figures from 1979—and that count was cut short after census-takers were killed by mujahideen.And:

Poor data afflict even the highest-profile international development effort: the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The targets, which include ending extreme poverty, cutting infant mortality and getting all children into primary school, were set by UN members in 2000, to be achieved by 2015. But, according to a report by an independent UN advisory group published on November 6th, as the deadline approaches, the figures used to track progress are shaky. The availability of data on 55 core indicators for 157 countries has never exceeded 70%, it found (see chart).Fortunately, there are now efforts to improve the situation (cited in the article):

A volunteer effort called Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT) improves maps with information from locals and hosts “mapathons” to identify objects shown in satellite images. Spurred by pleas from those fighting Ebola, the group has intensified its efforts in Monrovia since August; most of the city’s roads and many buildings have now been filled in (see maps). Identifying individual buildings is essential, since in dense slums without formal roads they are the landmarks by which outbreaks can be tracked and assistance targeted.

On November 7th a group of charities including MSF, Red Cross and HOT unveiled MissingMaps.org, a joint initiative to produce free, detailed maps of cities across the developing world—before humanitarian crises erupt, not during them. The co-ordinated effort is needed, says Ivan Gayton of MSF: aid workers will not use a map with too little detail, and are unlikely, without a reason, to put work into improving a map they do not use. The hope is that the backing of large charities means the locals they work with will help.

In Kenya and Namibia mobile-phone operators have made call-data records available to researchers, who have used them to combat malaria. By comparing users’ movements with data on outbreaks, epidemiologists are better able to predict where the disease might spread. mTrac, a Ugandan programme that replaces paper reports from health workers with texts sent from their mobile phones, has made data on medical cases and supplies more complete and timely. The share of facilities that have run out of malaria treatments has fallen from 80% to 15% since it was introduced.

Private-sector data are also being used to spot trends before official sources become aware of them. Premise, a startup in Silicon Valley that compiles economics data in emerging markets, has found that as the number of cases of Ebola rose in Liberia, the price of staple foods soared: a health crisis risked becoming a hunger crisis. In recent weeks, as the number of new cases fell, prices did, too. The authorities already knew that travel restrictions and closed borders would push up food prices; they now have a way to measure and track price shifts as they happen.It seems to me that drones (remotely operated aerial vehicles), computers with geographic information system software, GPS technology, and cell phones represent a real technological solution to the need for better maps. Some donor (USAID) should leap on this and help to create better maps, that could be shared by the Internet and smart phones, for developing countries.

Labels:

Development,

foreign aid,

information,

SandT for Development,

Technology

Globalization is Recovering from a Mild Ailment - the Great Recession

I quote from an article in The Economist:

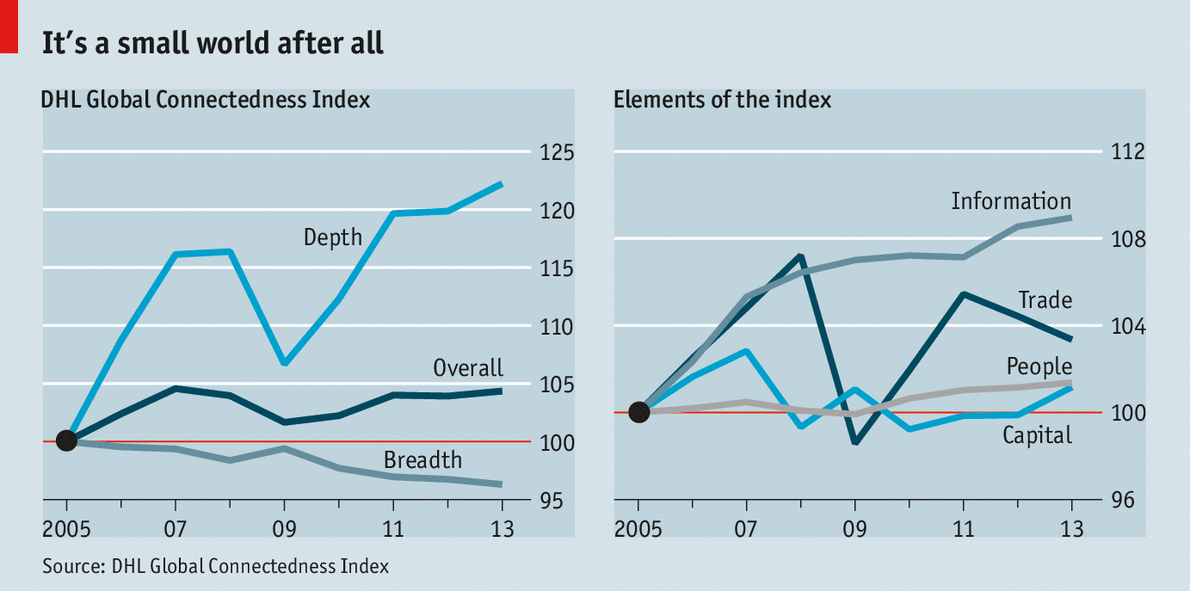

Globalisation’s advance has never been inevitable or smooth; nor, despite some backward steps since the crash, has it ended. That, at least, is the conclusion of the latest DHL Global Connectedness Index, published earlier this month.* Two economists, Pankaj Ghemawat of New York University’s Stern School and Steven Altman of IESE Business School compiled it using data from 140 countries, which account for 99% of the world’s GDP and 95% of its population. It shows that, after a big post-crisis drop, the trend of growing global interconnection resumed last year. Globalisation is back.

There are many definitions of globalisation, and the index uses one that is fairly all-embracing. It encompasses four main types of cross-border flow: trade (in both goods and services), information, people (including tourists, students and migrants) and capital. It tracks not just the depth of international connections (how much activity crosses borders), but also their breadth (how many different borders are being crossed) and their direction (how do outward and inward flows compare).World War I put an end to the first wave of globalization, that built on imperialism. I don't suppose people really thought that the Great Recession would end the second wave of globalization, which is based on capitalism and new technological infrastructures.

Labels:

Economics

Why the Pacific Counts in One Graphic

I quote from the article in The Economist:

Since the 1970s trade across the Pacific has far outrun the Atlantic sort. China, for instance, has taken its hunger for high-protein food and raw materials to Latin America and become the biggest trading partner of distant Chile. By one estimate, in 2010 it promised more loans to Latin America than the World Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank and the United States Export-Import Bank combined.

Labels:

Economics,

foreign policy

How I think.

A young cousin is doing research on dyslexia and got me thinking about how I think. As readers of this blog might know, I am interested in thinking anyway. Long in the past I did some neuro-modeling, and read some about brain science.

I think in words. Sometimes. however, I think about location in kind of a proprioceptive way -- imagining how I would reach out for something or point to something. I do not think in pictures. If someone asks me to visualize something I know well -- say the exterior of my house -- nothing happens. I remember the visual appearance of things in words; the door is brown, the siding is white.

I remember reading how a German chemist came about conceiving of the structure of the benzene molecule day dreaming about a snake devouring its own tail; that is difficult for me to even imagine; I just don't think in images, much less in animated images.

I can not spell well. Thank goodness for spell checkers on computers. When my second grade teacher sent home a message that she thought I was dyslexic (because I made letter inversions trying to spell words) my father decided to teach me how to spell. He said spelling was easy; you just visualize the word and write down the order in which the letters appear in your mind's eye. (He had a photographic memory, literally.) I don't have a mind's eye. His guidance was like telling a deaf person to listen to music and just write down the notes.

My wife does crossword puzzles and copy editing for pleasure; her sister used to be a professional editor, and her niece is now one. I think they have a different relationship to written language than I do; I simply don't see misspellings and I am very slow on language arts compared to them.

I am not very good at recognizing faces. If I recognize a face, but the person is met in a different context than usual, I am often at a loss for the name or the original context. Others seem to be better able to recognize a former child actor when that person is playing an adult role. Comparing myself to people I know well, my ability to link name to face seems definitely second rate.

I was trained as an engineer (many years ago) and of course took the basic course in engineering drawing. I did learn to infer the three dimensional form of an object from its two dimensional projections, but I do so by logical inference -- not be visualization.

I have learned to read graphs and like them. So too, I can follow the diagrams that others use to develop and explain their thoughts. However, I don't think I am especially good at dealing with these visual presentations. I have used Power Point in teaching and public speaking, but I don't think I am very good at the use of those aids. (I do think that Gapminder, which uses animated graphs and videos is brilliant.)

I am tone deaf, and have little ability to recognize music, even music I should know well.

I don't want to give the wrong impression. I have had a lot of schooling (BS, MSEE, Ph.D). I have traveled more than most people and read quite a bit. I am competitive and tend to do well on tests. For example, as a senior in high school I took the Iowa Test, used to measure educational accomplishments of the students of the Los Angeles School District; I was told I got the high score in the city. In my late 20s I took the Graduate Record Exam for entrance into grad school. It was then standardized, with a score of 500 for the average college graduate, with a range from 200 to 800. My total for three tests (verbal, quantitative and engineering) was 2430.

I seem to have a good memory for what is said. I can sit through a meeting, not take notes, and write a fairly coherent summary of what went on; people tell me that is rare. As a student I did not really understand why people took notes of lectures; I seemed to remember the salient points, and writing notes often seemed to be a distraction. At age 77 I am beginning to have more problem remembering names than in the past -- thank goodness for Google and I am using associative approaches more often. I sometimes search for a word, typically recalling the first letter.

I seem to be relatively good at logic. I did well on related courses from basic algebra, to deductive logic, to advanced calculus. At one time I was a pretty good bridge and chess player.

My doctorate major was operations research -- mathematical modeling for the solution of practical problems -- and I have worked with professional statisticians and economists. I have taken quite a bit of mathematics at a college and graduate level. I seem to be good at mathematical thinking.

I have a lot of background in computers, and at one time was a pretty good programmer. (The development of the field has pretty much made those skills unnecessary, and I have not used them in a long time.)

English is my native language, but I also speak Spanish (accented) and read French and (less well) Portuguese. Compared to people I know, my ability to learn languages is quite limited; my class actually drove our teacher to tears by mass incompetence in high school Latin.

I am aware that some of my thinking is not done by my conscious mind. I am not here writing only about reflexive actions, or the way subconscious desires may influence ones conscious thoughts and decisions. I have had the experience waking up thinking about something or seeing an answer in the morning to a problem I was mulling over in the evening. When I am pondering how to solve a problem, sometimes I "get a hunch" -- a feeling that if pursue a certain line of reasoning the problem will yield to analysis. Those hunches have led to discovery of new algorithms and new proofs. I assume the hunch comes as a result of stuff going on in my brain of which I am not consciously aware.

I have read that about 6 out of 10 people think primarily in pictures, about 3 out of 10 verbally, and among the remainder are kinesthetic thinkers, and "logical/mathematical thinkers (who learn via systems, categories and links) as well as a handful of other types." I would guess that I am primarily a verbal thinker, with a relatively strong component of logical/mathematical thinking and some kinesthetic thinking tossed in.

Sources of Mortality

Source: New England Journal of Medicine

Keep this chart in mind when you decide what to worry about. A life style that reduces the risk of cancer and heart disease is quite important; other risks may not be so great.

Of course, while you are driving, if you choose the drive fast under dangerous conditions, your risk of dying soon from an accident becomes much greater than if you are at home asleep in bed; if you are facing an unusual high risk, guard against it!

A couple of caveats in interpretation of the chart. One is that death from some causes, such as accidents, will take many more years of life from the average victim than would deaths from say Alheimer's Disease. The other is that the ease of risk aversion will differ greatly from cause to cause.

But I suppose the bottom line is "don't sweat the small stuff; focus on what really counts"!

Incidentally, are you not glad of the progress made in public health and medicine since 1900!

Labels:

Health

Sunday, November 16, 2014

How do ideas change in the law?

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. First Amendment, Constitution of the United States of AmericaI have just read The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed His Mind--and Changed the History of Free Speech in America by Thomas Healy. The dissent in the title was one in which Holmes, a Justice of the Supreme Court, dissented from a majority decision letting the conviction of people for an act of speech; instead he called for a broadening of the rights of free speech guaranteed under the first amendment.

Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was a Boston Brahmin. He had been a three times wounded soldier in the Civil War, in which he had also almost died of disease. A lawyer, he had served in the Massachusetts Supreme Court before Teddy Roosevelt appointed him to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1902. A complex man, often thought of as a conservative, but also with strong progressive leanings. Holmes would serve in the Supreme Court until 1932, but Healy's book focuses on 1918 and 1919.

The first amendment does not mean what it appears to mean to the lay person. It has always been accepted that the government had the right, indeed the duty to restrict some kinds of speech. There are laws against libel, slander, fraud, false advertising and incitement to riot. Espionage is illegal; there is no right to tell the military or diplomatic secrets of the nation to an enemy or potential enemy. There was a law against sedition in England when the Constitution was written, and a Sedition Act was made law in 1798 in the United States; that law however was severely criticized even in its own time as barring legitimate criticism of the government, and was allowed to expire in 1800; the fines levied under the Sedition Act were later refunded by the government.

The second decade of the 20th century was an uneasy one in the USA. In the election of 1912, three progressive candidates (Wilson, Taft and Teddy Roosevelt) had split the presidential vote and Socialist Eugene Debs had received 6 percent of the national vote. Not only were socialists visible in American politics, so too were Bolsheviks and Anarchists. Even before America entered the war there were German saboteurs functioning in the country (see Dark Invasion: 1915: Germany's Secret War and the Hunt for the First Terrorist Cell in America by Howard Blum). The Germans proposed that Mexico declare war on the United States (see The Zimmermann Telegram by Barbara Tuchman). American ships were sunk on the high seas, and then the United States did enter the war.

The Great War was fought from 1914 to 1918 on the Western Front, but it was the first world war with a level of casualties and deaths that exceeded all previous wars. Propaganda had charged the Germans with atrocities. And a flu pandemic stalked the world killing tens of millions of people.

The Decisions

In this environment the Espionage Act of 1917 became law as did the Sedition Act of 1918. These were quickly used to arrest, try and convict people and a number of cases arrived at the Supreme Court, beginning in January of 1919. Two issues were key:

- Were the laws constitutional. That is did they or portions of them contravene the constitution and especially the first amendment.

- If they were constitutional, what criterion should be used in defining whether an accused had actually contravened the law.

In the first of the cases to be decided (Schenck v. United States) Holmes wrote the unanimous opinion. I quote a section from that opinion:

We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done........ The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force.......... The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right. It seems to be admitted that, if an actual obstruction of the recruiting service were proved, liability for words that produced that effect might be enforced.This opinion defends the right of the Congress to pass this law, and suggests that creating a "clear and present danger" is a standard for decision as to whether someone has contravened the law or not. The judgment of the lower court was affirmed.

Less than a year later after several other cases, in Abrams v. United States, wrote a dissent. I quote from that opinion:

I am aware, of course, that the word intent as vaguely used in ordinary legal discussion means no more than knowledge at the time of the act that the consequences said to be intended will ensue. .........

But, as against dangers peculiar to war, as against others, the principle of the right to free speech is always the same. It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned. Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country. Now nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger that its opinions would hinder the success of the government arms or have any appreciable tendency to do so.......

Persecution for the expression of opinions seems to me perfectly logical. If you have no doubt of your premises or your power, and want a certain result with all your heart, you naturally express your wishes in law, and sweep away all opposition. To allow opposition by speech seems to indicate that you think the speech impotent, as when a man says that he has squared the circle, or that you do not care wholeheartedly for the result, or that you doubt either your power or your premises. But when men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas -- that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out. That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe and believe to be fraught with death, unless they so imminently threaten immediate interference with the lawful and pressing purposes of the law that an immediate check is required to save the country.He states, disagreeing with the majority, that "the defendants were deprived of their rights under the Constitution of the United States."

This dissent was disliked by many and cheered by a few when it was written, but by the 1940s a more liberal Supreme Court came to make it the basis for U.S. interpretation of the first amendment.

How Holmes Changed His Mind

Healy does a remarkable job of describing how Holmes' ideas evolved, drawing on letters, and diaries. He cites the key law journal articles and discussions with Learned Hand (another judge who handled one of the early cases in a lower court), Harold Lasky and Zackariah Chafee. He identifies the books Holmes read during 1919, especially those suggested by Lasky.

He can not, of course, discuss what went on in the secret meetings of the members of the Supreme Court. Nor does he go into much detail about the briefs and oral arguments related to the cases.

Of course, especially in our system, the law evolves through decisions on specific cases, and Healy is quite good at describing the details of those cases. We read that the conviction of Eugene Debs, a nationally known man who received millions of votes for president in 1912, was seen as much more serious than that of some Russian immigrants who printed a flyer advocating a national strike in arms and munitions factories and tossed copies from rooftops.

The end of World War I saw empires falling, monarchies dethroned. It was a war that evolved from secret treaties made by a thin ruling class in the countries of Europe. Americans had entered that war with an explicit objective of "making the world safe for democracy". The map of Europe was being redrawn to give nationalities the right of self determination. Perhaps that environment too encouraged Justice Holmes to see better the virtues of free speech and the dangers of the suppression of dissent.

I found myself wondering if author Healy did justice to the unusual qualities of Justice Holmes himself. Holmes was a man who like to discuss ideas. He was also aware that the law changed, and that it was through the scholarship and analysis of men like himself that the law evolved. He may have believed (probably did believe?) that as a general principle the most credible ideas emerged from civil and reasoned debate in "a marketplace of ideas". Holmes was a legal scholar of considerable repute, and I suspect that he was the most likely member of the court to promulgate this new standard in a dissent.

Healy writes about Holmes' travel, his walks, his vacations, his secretaries, and his wife's ill health. By the nature of his text, suggests that living in the world itself leads to changes in the way we think. The American participation in the war ended with the Armistice on 11/11, 1918, so the war thinking was much further in the past in November 1919 than it had been in the winter of 1918; Holmes had spent the intervening summer at his summer home on the Massachusetts coast. Moreover, federal, state and local government censorship of radical thought had increased greatly in 1919. Moreover, his friends Lasky and Chafee had been the victims of efforts to infringe on their academic freedom at Harvard University where both were faculty members. I would suggest that many factors combined as Holmes changed his mind about the right of the Congress to limit speech in times of war and the criteria to be used in determining guilt or innocense.

In his landmark dissent, Holmes was joined by Justice Louis Brandeis. There were subsequent dissents, joined by other justices over the years, until in the Franklin Delano Roosevelt era Holmes's view became the majority view. Still, the Supreme Court decisions on freedom of speech can be divided and controversial, such as was the recent Citizens United decision.

Final Comments

I found this a very stimulating book. It deals with important questions: How do men in power come to change their minds on important issues? What kind of man can do so at all? I think the example in this case -- of one judge, followed by another more influential judge, followed by others -- is very useful for the reader to to know and understand.

I would point out that censorship is still with us. Yesterday I came across this article suggesting that The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne and A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway are even today being blocked by officials in Texas who wish to limit what students can think and read.

Culture wars are being fought today. There are those in Congress who would reduce funding for research on climate change, the danger from firearms and political science because they fear that they might not like the results of such studies. There are those who would promote the study of creationism in schools and a mythical history of the USA rather than a more accurate one, because they are afraid of the marketplace of ideas. The Great Dissent should encourage us to question such policies.

Labels:

book review,

History,

thinking

Saturday, November 15, 2014

More on Ebola in western Africa

Forbes magazine is publishing a three part series written by Farai Gundan on the Ebola epidemic in western Africa. Here are links to the first two articles:

- LIBERIA: How Africa And Africans Are Responding To The Ebola Crisis

- Guinea: How Africa And Africans Are Responding To The Ebola Crisis

I will add the third article as a comment when it is published. (This seems to be the 3rd article: "Billionaires Aliko Dangote, Strive Masiyiwa, Patrice Motsepe Join Fight Against Ebola".)

I have been reading and hearing about U.S. and European efforts to help contain the Ebola epidemic, but these articles describe the efforts of African civil society organizations, African regional intergovernmental organizations, and wealthy African individuals to do so. These are the folk with most to lose immediately, and the most local knowledge to share.

UNESCO is also starting a project, drawing on its considerable skills in media and its knowledge of community radio, to do health education in the affected area.

Labels:

Ebola

Thursday, November 13, 2014

Where Did All the Money Go in the Recovery? To the Rich.

For a long time, most of the gains from economic growth went to the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution. And, after all, the bottom 90 percent includes the vast majority of people. Since 1980, that hasn't been the case. And for the first several years of the current expansion, the bottom 90 percent saw inflation-adjusted incomes continue to fall.

The data series ends in 2012 and we don't know how long the expansion will last, so that negative income trend may evaporate before all is said and done. But unless there's a massive break with the previous three expansions we will continue to have an economy where the typical family's living standards grow much more slowly than GDP growth per se would allow.The chart was first posted by Pavlina Tcherneva. an economist working a Bard College and the Levy Economics Institute.

Note that the chart only deals with periods of expansion.

I repeat a point I made in an earlier post. To fully understand the situation you have to look not only at income but also at changes in wealth. The people with the highest incomes tend to be also the people with the greatest wealth. The stock market has boomed since the depth of the Great Recession, and the value of the investments in stocks have greatly increased. For the stocks that the rich simply held, the increase in value is not counted as income; only when they sold a stock and took a profit was that profit counted as income. Indeed, rich people who at the bottom of the market traded a stock that had lost value since it was purchased and bought a comparable stock with the proceeds of the sale may have seen both a big increase in wealth and obtained a write off against income.

On the other hand, for many of the 90%, their wealth has gone down with the Great Recession and not recovered. These are people who lost jobs and had to live on savings, who had mortgages foreclosed and lost their homes, and people who are paying mortgages on homes that are still under water. Not only have they on average not benefited from the recovery, but they are still suffering from the losses that they took as a result of the Great Recession.

Labels:

Economics

The big players are growing their R&D expenditures.

OECD says:

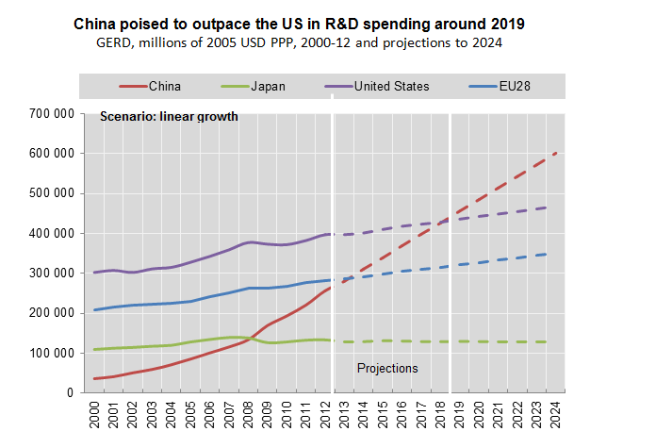

- Squeezed R&D budgets in the EU, Japan and US are reducing the weight of advanced economies in science and technology research, patent applications and scientific publications and leaving China on track to be the world’s top R&D spender by around 2019, according to a new OECD report.

- The OECD Science, Technology and Industry Outlook 2014 finds that with R&D spending by most OECD governments and businesses yet to recover from the economic crisis, the OECD’s share in global R&D spending has slipped from 90% to 70% in a decade.

- Annual growth in R&D spending across OECD countries was 1.6% over 2008-12, half the rate of 2001-08 as public R&D budgets stagnated or shrank in many countries and business investment was subdued. China’s R&D spending meanwhile doubled from 2008 to 2012.

- Gross domestic expenditure on R&D (GERD) in 2012 was USD 257 billion in China, USD 397 billion in the United States, USD 282 billion for the EU28 and USD 134 billion in Japan.

These estimates are not purchasing power adjusted, so countries with lower costs of doing research and development will be under reported here, and those with higher costs may be over estimated.

The data don't at this level separate fundamental research (with results that will be published openly and available in all countries) versus proprietary R&D that may well give a country an advantage in international trade. The growth of Chinese (and Indian) support for fundamental research should be a good thing, benefiting people in all countries; essentially China with its long term rapid economic growth is assuming a more proper place relative to its huge population in the production of scientific knowledge and understanding. On the other hand, the United States might be well advised to seek ways to increase its R&D for the production of new technologies to meet coming challenges from other nations.

Of course, there is an argument that the growth of the global economy is "a tide that lifts all ships". More affluent people buying more goods and services on international markets can mean a better life in all nations.

Labels:

science

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

We need some changes to the Constitution

Did you know that states, with their constitutional powers, can allocate their electoral votes in presidential elections as their legislatures choose. Most have all the electors vote for the candidate who gets the most votes in their state.

But that is not required. In Maine and Nebraska, two electoral votes go to the candidate who gets most votes in the whole state, and one electoral vote goes to the candidate who gets most votes in each Congressional district. Thus in these states electoral votes are often split.

Now we know that in red states, most of the voters are rural or small town residents and the Republican majority takes all. In blue states, most voters live in big cities, and the Democratic majority takes all.

What would happen in a close election if Republicans controlling the state government of a slightly red state were to switch to the Maine/Nebraska like system? Well Republicans would likely pick up some electoral votes -- those from the rural districts in the state.

Might they really do that? Might that work? Read this!

Labels:

election

Tuesday, November 11, 2014

About the Federal election of 2014

The federal election is reported to have cost nearly $4 billion, but apparently that does not include the so called "black money" that is not accounted. (Apparently, non-profit organizations of some kind are now funding adds and other election related expenses, and while they are theoretically required to report these to the Bureau of Internal Revenue, they are not doing so -- the so called black money.) I have heard it estimated that black money may have added $2 billion to the campaign chests.

Only 36.6 percent of the electorate turned out to vote, and there are many Americans who could register to vote who do not do so. The article says:

For reasons that include the sorting of the electorate into like-minded folks, redistricting and the cultural divide between cities and prairies, only 5% of the House’s 435 districts were truly competitive on November 4th. There were 69 congressional districts where the candidate faced no opponent. This means that the main threat to the jobs of congressmen comes from primary elections, in which fewer than 20% of the electorate vote, about the same proportion who describe themselves as holding consistently conservative or consistently liberal views. Few congressmen lost to primary challengers in 2014, but results like the defeat of Eric Cantor, the House Majority Leader, in Virginia’s seventh district remind them that such voters are not wild about anything that smells of compromise with the other side. These voters have the first veto.Thus a small minority of adult Americans actually elect the members of the House of Representatives. The voters who actually matter are probably not representative of the public at large. I would bet that they are often poorly informed on the issues, depending frequently on sources of education that pander to audiences with narrow ideological spectrums of views (e.g. Fox News and MSNBC). The Congress had an 11% approval rating, but 96.4 of the candidates running for reelection were in fact reelected.

Getting a bill safely through the House, something that has become harder since Republicans adopted the idea that bills should have the support of a majority of their caucus to pass, is straightforward compared with getting one through the Senate, thanks to the filibuster rule. Since a filibuster requires a bill to gain a 60-vote majority, a group of 41 senators can halt almost any piece of legislation. Even the smallest state has two senators, so those 41 sometimes represent a small chunk of the electorate: Larry Sabato of the University of Virginia has worked out that states that are home to just 11% of Americans can elect the senators needed to block legislation. This potent weapon gives the minority party in the Senate the second veto........

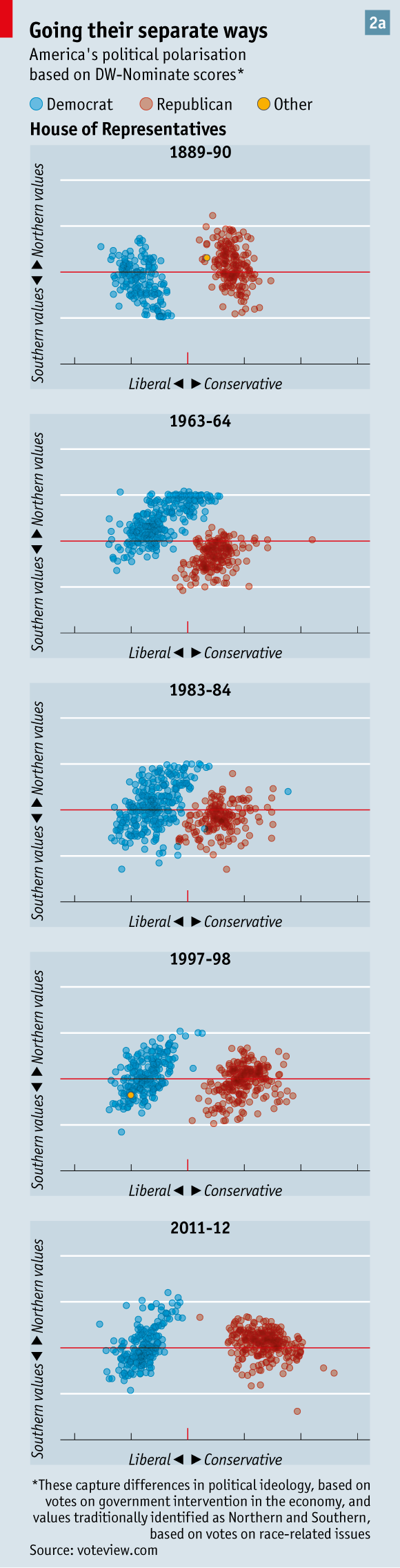

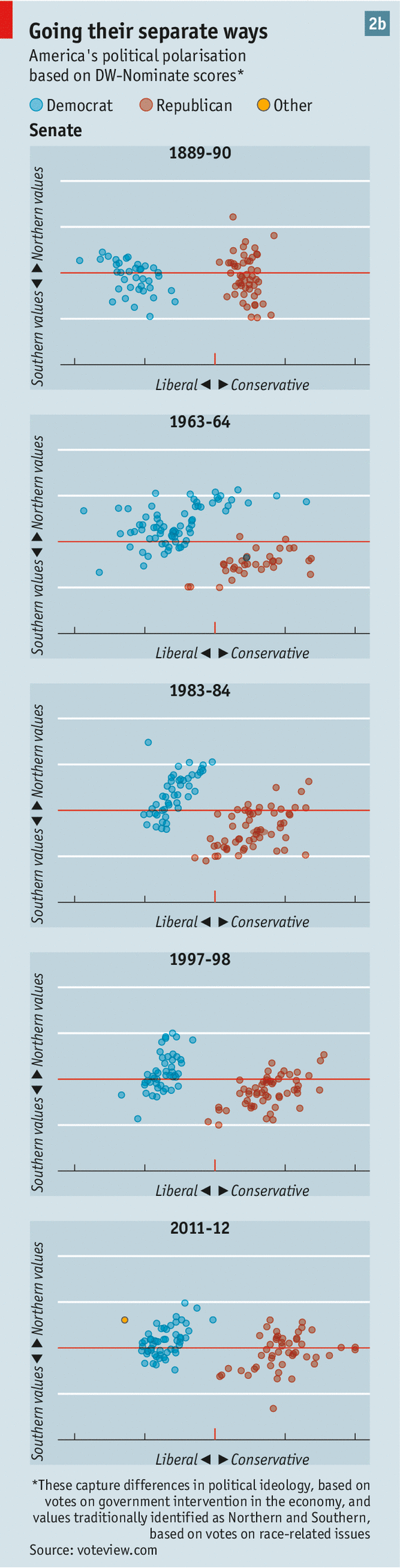

Congressional Republicans and Democrats have withdrawn from each other, to the point where there is now hardly any common ground between them (see chart 2).

Voting patterns in Congress suggest that the parties are even further apart now than they were in the mid-1990s, when Republicans tried to impeach Bill Clinton, or the middle of the past decade, when Democrats denounced George W. Bush as a warmonger.While the cost of this election was higher than ever, this election saw a reduction of the number of donors. The Stayers apparently contributed nearly $74 million during this election cycle; Micheal Bloomberg more than $20 million; with many others contributing one to several million dollars each.

I find it embarrassing that democracy seems to be working so poorly in the USA. This country fought in a couple of world wars with a stated objective of making the world safe for democracy. We spent a decade, trillions of dollars and thousands of American lives supposedly in an effort to spread democratic institutions to Iraq and Afghanistan. American exceptionalism has been proclaimed for many decades. In our greatest speech, President Lincoln said about the Civil War, our bloodiest,

that we here highly resolve these dead shall not have died in vain; that the nation, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.He was a realist and a practical politician, but how would he feel a century and a half later about the state of our government? How much are the people of other nations laughing at our pretensions of a government of the people, by the people, and for the people?

Measures that matter -- for international comparisons

I quote from an article in The Economist (which is also the source of the above chart):

(P)erformance indices, which rank social issues or policy outcomes in different countries by combining related measures into a single score for each, are enjoying a boom. Their number has soared over the past two decades (see chart). For many issues, rival indices must now battle it out......

The best indices are meticulous (PISA, for instance, combines dozens of carefully standardised sub-measures and raises statistical caveats). But others are based on shaky figures that are calculated differently in different countries. And choosing what to include often means pinning down slippery concepts and making subjective judgments. An index of democracy, freedom or happiness means putting hard numbers to the fairness of elections, weighing civil liberties against economic rights, or deciding how much to rely on surveys.The article goes on to discuss work by Judith Kelley of Duke University and Beth Simmons of Harvard University on the Trafficking in Persons (TIP) index "first published in 2001. That year’s annual report covered 79 countries; it now ranks almost 190." The publication of the index data is described as having influenced countries to pass laws against trafficking, but the report as suffering from difficulty in accurately measuring the numbers of persons trafficked.

Of course, the indicators and reports are not of uniform quality. Some, such as the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which rates 15-year-olds’ academic performance in dozens of countries, are very good indeed. Others require a fairly high degree of sophistication to properly understand and utilize.

Indicators are hard work! It is hard to choose an indicator that is measurable, for which the measurements will be reasonably accurate, that will be policy relevant, and that will be reasonably well understood by the policy makers who are to use the data.

- GDP, for example, leaves out the product of unpaid services (such as those done by family members in the home) and can be very inaccurate in measuring the product of the informal economy, and even less so in measuring the product of illegal activity.

- Employment is difficult to interpret as one deals with people who want jobs but are too discouraged to actively seek them, people (such as retirees) who would work if approached with the right jobs but who don't respond that they want work, people who work part time (especially in more than one job), and people who work in the informal economy, in subsistence agriculture, and in the illegal economy.

- Health: while WHO has promoted the use of disability adjusted life years (DALYs), I don't think it fully captures the burden of illness, nor is fully useful as an instrument for policy makers.

- Happiness has been experimented by some countries and researchers, but has obvious problems, especially in comparing one cultural group against another (say a phlegmatic group versus a vocally complaining group).

One wants indicators to be used consistently over time so that policy makers can see the overall trends and understand the impacts of their policies; one also wants to update indicators to take advantage of improved theory, understanding, and data collection methods. Unfortunately, the two objectives are mutually incompatible.

Still, I think the availability of more indicators and more reports giving international comparisons based on the best available data is likely to be a healthy trend. After all, there are different audiences for the different reports, and we all like to do well as compared with our peers.

Labels:

indices

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2459894/leading_CODs_1900_2010.0.jpg)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/1400916/BuX2fpzIAAAZc77.0.0.jpg)